How tariffs actually impact U.S. module manufacturers

The question that the Department of Commerce is not charged with answering in the anti-dumping circumvention investigation is whether or not these additional duties actually help U.S. solar manufacturers “compete.”

Sales and marketing month sponsor

Get Aurora AI & Get Back to Summer

Let Aurora AI do the heavy lifting for you so you can get out of the office and into the pool. See how Aurora can speed up your sales & design with one-click design magic. Learn more here

“At a distance this might look like a good thing for U.S. manufacturers, but they might not be thinking about where we buy cells from,” says Martin Pochtaruk, CEO of Heliene, which produces just-in-time modules from three, soon to be four, North American facilities.

Until now, Heliene bought most of its cells from factories in the four Southeast Asia countries named in the investigation. This is fairly common. Last year, 46 percent of cells imported by U.S. manufacturers came from these countries. Pochtaruk says competing against imports goes well beyond the domestic supply of solar cells.

“The difference between us and our competition, which is mainly imports and much larger companies, is they have working capital financing and low interest rates, mainly from the Chinese government,” he says. “Those companies can afford to manufacture a product, ship it and sell from that port. We are not 12 to 14 weeks of shipping away. We put it on a truck and you can get it next morning.”

Heliene started slowly selling into the residential market via its Mountain Iron, Minn., facility in 2018. In 2021, it opened another spot in Riviera Beach, Fla. They now sell about 17 to 20 percent in residential and small C&I, with the rest in the 5 MW to 20 MW ground-mount space.

Since the announcement of the trade case investigation, Heliene has found a new cell supplier, which helps keep its doors open, but the previous cell was approved within its certification. So, the switch has caused headaches, but he’s also not sweating Commerce’s decision.

“Nobody knows where they will find modules, or if there is enough volume to accommodate, and then in a few months we’ll all find a solution,” he says. “Modules are being exported from India, Turkey and Canada that many companies have bought from before. There are others in Southeast Asia that have capacity that might not yet be known to developers but will be known soon enough.”

To his point: In 2018, when Donald Trump placed Section 201 tariffs on all module and cell imports, trade groups expected PV prices to skyrocket, but they didn’t. “Equilibrium was achieved within a quarter,” he recalls. In 2018 and 2019, the price was the same in absolute terms because international pricing was already falling. U.S. trade duties haven’t impacted the global price or supply of PV modules for buyers.

The negative impact of cumulative tariffs on U.S. module production

For Solaria however, a 250-MW module producer headquartered in California that has its manufacturing setup overseas, shockwaves from the Section 201 tariffs are still being felt.

“That’s one of our biggest expenses,” says Suvi Sharma, founder of Solaria and now CEO of SOLARCYCLE, of the Section 201 tariffs. Its manufacturing is based in Korea, and Solaria primarily sources from Korea and Taiwan, which has AD/CVD duties of under 2 percent. “We had to reduce R&D expenditures because we’re paying so much in tariffs. It’s still our single biggest line item.”

Solaria makes a premium module primarily for the U.S. residential market. Sharma admits the Section 201 tariff somewhat influenced the desired behavior when several module companies set up assembly plants in the United States (not all have lasted). His company was considering it too, especially after the Section 201 tariffs were extended another four years by the Biden Administration.

That potential U.S. expansion plan has several challenges though, and they illustrate how a domestic strategy built mostly on duties and tariffs doesn’t influence much immediate or impactful on-shore business:

The AV/CVD trade case. Solaria has not, in the past, bought cells from the four countries in the investigation, but it was going to as part of a prospective expansion plan.

“The AD/CVD investigation, for us, is creating chaos,” Sharma says. “Primarily in terms of future expansion plans. We have been working on expansion plans at Solaria that involve purchasing solar cells from some of the countries under investigation. So, that puts those on hold at the very least until we see the outcome. … It depends on what the assessed duties will be, but ultimately, we’ll end up with higher costs and lower margins — some will get passed on to business and consumers.”

Section 201 tariffs. Under the safeguard measures extended by the Biden Administration, solar cells are subject to a tariff-rate quota (TRQ) so that a certain volume can be imported each year before tariffs are triggered. That TRQ has been increased from 2.5 GW to 5 GW, which is a lot. The current rate of 14.75 percent for 2022 declines 0.25 percent per year.

Section 301 tariffs. Like Section 201, these are trade remedies that ding backsheets, aluminum for frames, wires, encapsulants, solar glass, etc., from China, all at 35 percent.

“A lot of the calculating you end up doing is if you make panels here, you avoid the 201 tariffs, which is 15 percent,” Sharma says. “But then you have to source the glass and frames and other components outside of China, and with the higher labor costs in the U.S., it can add up to greater than 15 percent.”

Even outside of China, Heliene is nickel-and-dimed with duties. The backsheets they source from Italy carry a 5 percent import duty.

“These safeguards are supposed to create manufacturing capacity in the U.S. — and we did do it; we invested in the U.S.,” Pochtaruk reminds. “However, the 301 safeguards were put in place to make our cost higher, and we are still dealing with that.”

Oh, and all that money being collected from the Section 201 tariffs to help even the playing field for the domestic solar industry? More than $2 billion has been collected on that 15 percent tariff and none of it has gone to the solar industry. In 2016 a law was passed saying the collection of tariffs cannot benefit the industry members. It goes into the United States general treasury fund.

Lack of U.S.-based supply chain

U.S.-based facilities would help Solaria for sure because the United States is its primary market. They’d have better time to market, more proximity to customers, simplified logistics and easier inventory management.

“But the bulk of our materials have to come from overseas,” Sharma reiterates. “The shipping costs are high, and then compound that with the fact we can’t use some of the same suppliers we use in Korea. We would need to come up with a new supply chain that’s U.S. specific … the complexity goes up, especially in solar where the margins are so small, it can kill you unless you’re a big company.”

When lamenting the rising price of PV modules, these issues need to be kept in mind too. Tariffs are used as a market correction tool to aid domestic industry, but for U.S. solar module makers, since most module components must be sourced off-shore, these protectionist trade measures are simply raising costs and making it harder to be competitive.

“Glass is my pet peeve these days,” Pochtaruk says. The glass of a solar module is specially produced for the purpose with no iron content, which requires a special sand. That glass comes mainly from China and Malaysia. “We continue to pay roughly $4 per sq meter of glass. The cost of glass itself is about that. But two years ago, shipping from China or Malaysia for a sq meter of glass was 10 percent of that. Now, the transportation for each piece of glass is around $20. For the same piece of glass.”

Solar manufacturing incentives

Slowly, domestic supply chain is coming online. Endurans Solar is producing backsheets in New Hampshire (formerly DSM). Minnesota-based H.B Fuller placed a massive investment to increase its volume of encapsulants. Canadian Premium Sands is working to build a solar glass factory at the U.S. border.

“There has been, historically, glass manufacturing for solar in the U.S. There is and there has been, historically, backsheet manufacturing in the U.S.,” says Paul Wormser, VP of Clean Energy Associates (CEA). “But now you have to get into the question of: Is the supply enough? Is the pricing competitive? Is the spec something that can be met? And this is where many of the players in the U.S. supply chain have lost market share over time or they have just exited the solar business. It doesn’t mean they can’t come back.”

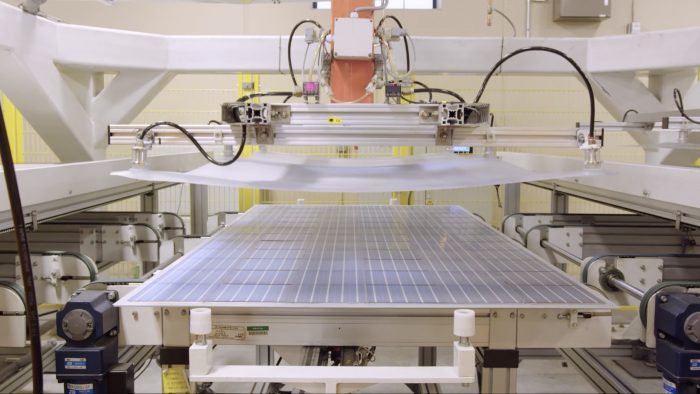

Wafers, cells and glass are extremely capital intensive. If additional duties are placed on a major source of solar cells, and if that, in a best case scenario, incentivizes U.S. solar cell production, that plan will take years to build out. See the chart below. Plus, if you’re building a GW-scale solar cell production facility in the United States today, you will still be sourcing the ingot and wafers from China, which carry their own 35 percent import duty.

“Thinking that local manufacturers will be protected from imports is wishful thinking. You can’t count on being eternally protected from imports. We need to improve costs, efficiencies, etc., to compete,” Pochtaruk says.

Domestic module component outlook

- Solar glass: Pilkington (only First Solar) otherwise, nothing is online today. Canadian Premium Sand is building capacity soon, mainly for the U.S. market.

- Backsheets: Supply from Endurans Solar.

- Encapsulant: Limited supplies from STR Solar, emerging supply from H.B Fuller.

- Silane: There are likely manufacturers, but no one is catering to PV since there is no cell manufacturing domestically.

Forecast: If some of the new, announced facilities materialize (Qcells, Maxeon, NanoPV, SPI, Reliance, etc.), more supporting infrastructure may arise.

Source: Clean Energy Associates

Some U.S. manufacturers will lament the unfairness of competing in the market against companies in other countries that subsidize production or dump prices. But, in a classic Catch-22, everyone seems to agree that incentives from the U.S. government are the only way to truly build out a domestic solar supply chain. The stalled Solar Energy Manufacturing for America Act would include economic offsets to incentivize not just solar cell manufacturing investment but wafers and even polysilicon. Qcells specifically announced plans to invest in everything from U.S. polysilicon to completed panel assembly, pending the passage of that bill. Otherwise, these are all too capital intensive to undertake on their own, with no certainty on costs or the future of U.S. energy policy / trade protectionism.

When President Biden initiated a safe harbor from new tariffs related to this investigation for two years, he also invoked the Defense Production Act to drive U.S. manufacturing of solar technology with the support of loans and grants. The administration says it can triple solar energy manufacturing in the U.S. by 2024; industry analysts have downplayed how impactful this move really is. But, it is something.

“Say if we had large R&D grants to see how to take solar cell efficiency to 24 percent, 30 percent — that would actually make things happen,” Sharma offers. “But this protectionism, I don’t see investors getting excited about investing in solar cell manufacturing because they would be worried that this all could change depending on the administration. We need a long-term industrial support policy.”

“Right now, with nothing happening, we plan to add another line in 2023. That’s 1.3 GW by next summer. Without SEMA,” Pochtaruk says. “With that inventive passed by Congress though? It will turbocharge what we already have.”

Chris Crowell is the managing editor of Solar Builder.

Comments are closed here.