First Nations lead Canada’s solar shift

Federal funding, local developers, and community training are helping Indigenous projects replace diesel and build lasting clean energy capacity

The 600+ First Nation indigenous communities in Canada are adopting solar projects at an increasing pace, thanks to Crown and to Provincial programs that encourage local energy team development and finance projects through grants and loans.

Much of the impetus for Native solar in Canada comes from Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), which recently launched the Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative to support 14 Indigenous clean energy projects, providing over CDN$28 million. This initiative includes collaboration with the Indigenous Clean Energy Social Enterprise and the Pembina Institute, a nonprofit clean energy institute known for its renewable energy planning work.

Among key goals, NRCan is seeking to replace diesel-fired generators in rural and remote communities, which are defined as “a community not currently connected to the North American electrical grid nor to the piped natural gas network, and which is a permanent or long-term (5 years or more) settlement with at least 10 dwellings,” the agency says.

Subscribe!

Have you subscribed to Solar Builder Canada yet? It’s free, ya know. And just for Canada! Sign up here.

The universe of such remote settlements in Canada includes at least 358 locations, according to the Atlas of Canada – Remote Communities Energy Database. Pembina has analyzed the cost of diesel use among these communities and found that “on average, remote communities pay six to ten times more for electricity and heat than other consumers. Without subsidies, energy costs in these communities would be 10 to 30 times more expensive.”

Overall, the Crown spends CDN$300 million to $400 million on annual diesel subsidies to bring down the high cost of electricity in remote communities, among which 79% of all energy generation is based on diesel, Pembina reports.

Installers specialized in remote projects

One Canadian installer specialized in remote and Native community solar projects is Solvest, based in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory. This spring, Solvest commissioned the Saa/Se Energy IPP owned by Copper Niisuu LP in Beaver Creek, Yukon. “This is the first remote grid in Northern Canada that will now produce over 50% of the community’s annual energy needs,” says Lauren Humble, Chief Business Officer for Solvest.

A few years ago, Solvest developed North Klondike, the “first megawatt-scale, grid-tied independent power production (IPP) project in northern Canada,” the company says.

The 1 MWac fixed tilt array is comprised of 4,000 bifacial solar modules, the project profile indicates. “The modules are facing south with an angle of 30 degrees to the horizon, and 7 meter spacing between the rows, and the foundation consists of iron piles driven 15 feet into the ground to support galvanized steel racking.”

Crown support for remote and Native solar

A key Crown program aimed at expanding remote and Native solar is the Clean Energy for Rural and Remote Communities Program (CERRC), which is “committed to improving access to federal funding and resources in Indigenous, rural and remote communities for clean energy projects,” the group says.

Launched in 2018, the CERRC program was allocated $220 million over 8 years to reduce reliance on diesel for heat and power in Indigenous and remote communities. CERRC received an additional $233 million over 5 years through Budget 2021. The program has supported 111 projects nationally, including capacity building initiatives, large capital projects, innovation projects, and bioheat projects.

One recent round of CERRC solar project financing includes the upcoming $1.2 million Solar North Expansion project in Haida Gwaii, British Columbia, for a doubling of the existing 2 MW solar array, managed by native developer Tll Yahda Energy (TYE). This company was formed by the Old Massett Village Council, the Skidegate Band Council and the Council of the Haida Nation. Many such locally dedicated energy developers are created in Indigenous communities as they form a formal local energy strategy, with the help of Crown and Provincial programs and groups like Pembina.

The first phase of the CDN$8.5 million Solar North project — 100% owned by the Haida Nation — was expected to reduce diesel usage by about 8.5% on the northern grid, said Nang Hl K’aayaas Sean Brennan, the project implementation manager for TYE, in a tribal project report. “If we get to 100% off diesel on Haida Gwaii, we would reduce diesel emissions in BC by about 51%,” he said.

The second phase doubling of Solar North will help TYE fulfill its mandate to reduce local diesel emissions by 100% by 2030. “If our goals are achieved, BC would be on track to achieve their goal of reducing emissions by 40% by 2030, and BC Hydro would achieve 51% of its goal of 71% emission reduction in the non-integrated area by 2030,” Brennan said in the tribal report.

Urban solar benefiting Native and non-Native communities

Apart from the groundswell of remote solar projects in Native communities, there is also a rise in the adoption of solar in urban locations benefiting both Native and non-Native residents. One Canadian solar company focusing on this market is Gridworks Energy Group, a 100% indigenous-owned and operated renewables company based in Edmonton, Alberta.

“Our most recent project is a 200 kW rooftop and pergola-mounted project for the Boyle Street Community Service shelter in Edmonton,” says Randall Benson, founder and owner of Gridworks, not associated with other solar companies with similar names, he notes. “The shelter offers temporary support and housing for homeless, recovering addicts and others in need of help.”

Native projects represent between 25% and 50% of Gridworks’ total business, says Benson, who identifies himself as “an Indigenous entrepreneur proudly of Cree, Iroquois, and Métis heritage.” Apart from solar installation activity, Benson is part of the Canadian solar industry standards and certifications committees, including the CSA Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Systems Certification (SPVC – NOC 7241).

Native solar projects often include requirements for local training and labor. Recognizing this, in 2009, Benson established “one of Canada’s first comprehensive solar PV design and construction training programs,” he says. Over 3,600 solar professionals from Canada and abroad have been trained in the program, “many of whom have gone on to establish their own successful solar businesses — some even becoming Gridworks Energy competitors,” he notes.

Incentives outlook for Native solar

Soon, the prospective Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit (ITC) could become law. Not to be confused with the 30% Clean Technology Investment Tax for commercial solar + storage projects, this Clean Electricity ITC would be a 15% reduction in system costs for nonprofits and non-taxpaying entities, such as indigenous communities.

Some provinces have established strong solar adoption incentives, like Nova Scotia. The province has sponsored the SolarHomes Program, administered by Efficiency Nova Scotia, offering a rebate of CDN $0.60 per Watt for solar systems, up to a maximum of $6,000. Along with this incentive, the Province has also launched the Home Battery Pilot, which provides rebates of CDN $300/kilowatt-hour of installed energy storage capacity, with a maximum rebate of $2,500.

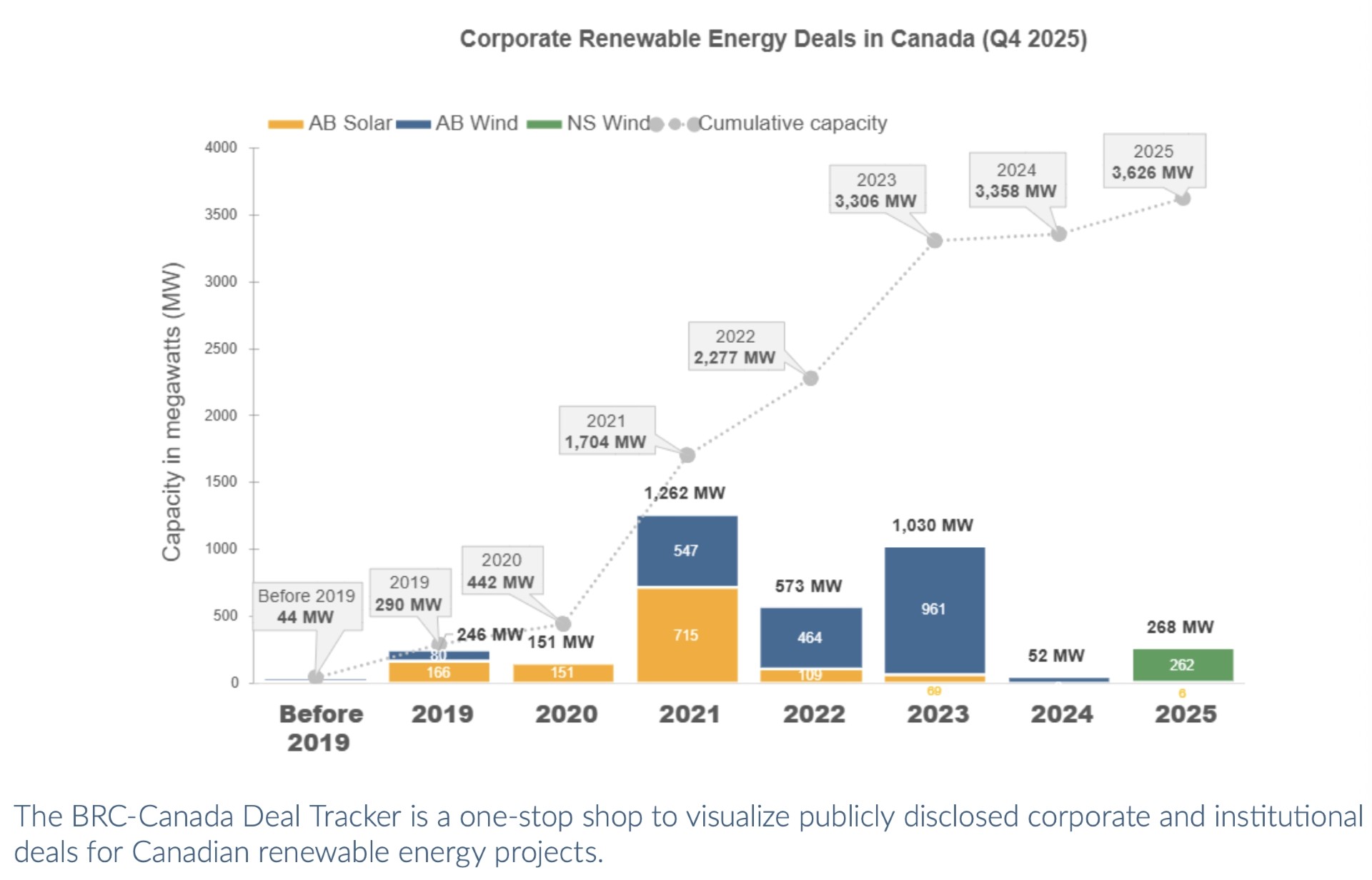

Other Provinces, like Alberta, have backed away from prior administration efforts to support solar adoption.

“The outlook in Alberta is pretty awful right now,” laments Benson. “The current Province has made it more difficult to do solar, after the prior government supported it. There are estimates that some CDN$34 billion worth of wind and solar projects have left the Province.” Gridworks is in the process of opening its first office in neighboring British Colombia Province.

Regardless of the location, Native solar projects tend to take longer to execute, but also tend to be completed. “Community engagement is a vital piece of each project execution through information sessions, training and employment,” says Humble.

Charles W. Thurston is a contributor to Solar Builder

Comments are closed here.