Filling Unused Land with Solar

The landfill and brownfield market is growing for solar installations, and SunLink has worked out a system that will last.

Massachusetts isn’t that big. It’s the seventh smallest state in the union, and the only states it beats are its surrounding New England friends. But it’s the 14th state by way of population — more than 6.5 million people call the Bay State home. The state’s population density is third in the nation with 840 people per square mile. That’s a lot of people on top of each other; space is tight.

Now consider that Massachusetts has 594 inactive or closed landfills and 23 still actively filling with waste. That’s a lot of uninhabitable land in a state that seems pretty crammed. Parks, shopping malls and golf courses have been built on old landfills, but there are often settlement issues or reports of methane gas escaping when not properly monitored. The better and safer option for these brownfields? Solar installations.

Massachusetts knows this. The state has installed more than a dozen in the last few years — Washington Gas Energy Systems built six, Gehrlicher owns a few, Clean Focus recently announced 19.5 MW of new projects, and Borrego Solar has used its PPA experience to construct solar on capped landfills, too. In 2012, Borrego worked with mounting system manufacturer SunLink on two projects in the towns of Ludlow and Easton.

Massachusetts knows this. The state has installed more than a dozen in the last few years — Washington Gas Energy Systems built six, Gehrlicher owns a few, Clean Focus recently announced 19.5 MW of new projects, and Borrego Solar has used its PPA experience to construct solar on capped landfills, too. In 2012, Borrego worked with mounting system manufacturer SunLink on two projects in the towns of Ludlow and Easton.

Constructing solar on capped landfills requires a certain expertise and knowledge of the many installation issues that can arise — differential settlement, weight limits and increased expenses, to name a few. But SunLink has the experience, says Yury Reznikov, vice president of product and strategy.

“We’re warranting these products for 15 to 20 years, so we’ve learned a lot about how to install them, how to make sure the landfill caps survive for the next 15 to 20 years,” he says. “We believe our solution is one of the few that is going to be out there for the long term.”

LIGHTWEIGHTS

When you see a capped landfill, it often just looks like a large, grassy field; you wouldn’t know there’s a mound of trash hiding underneath. Although the ground looks fairly normal, a traditional penetrating ground-mount solar installation won’t work, says Joe Harrison, senior project developer at Borrego Solar.

As landfills fill up with trash, areas are compacted and covered with layers of soil and sand. Generally since the late 1980s, landfills in the Northeast have been capped with a geomembrane lining. About 2 ft of soil is then spread on top of the cap and grass is grown. Vegetation is monitored annually to ensure root systems don’t damage the cap.

Two feet of soil is nowhere near deep enough for a penetrating system, and since nothing can puncture a landfill cap, ballasted is the way to go when installing solar at landfills. But even weight is a concern on top of that geomembrane film.

Two feet of soil is nowhere near deep enough for a penetrating system, and since nothing can puncture a landfill cap, ballasted is the way to go when installing solar at landfills. But even weight is a concern on top of that geomembrane film.

“Our ballast blocks are around 1,500 lbs a piece, so it doesn’t create an issue for the cap, but the challenge is moving them around and getting them in place,” Harrison says. “We have a staging area during construction off of the cap, then only tracked equipment is moving around on the landfill. When you have a [machine] pick up a ballast block and start driving around, the point load on all four tires is too great for the landfill and cap. You have to use tracked equipment to spread out that weight.”

SunLink is a big proponent of pre-panelization — the act of assembling systems off-site to speed installation and cut down on unnecessary weight loads on unstable ground. Its two ground-mount systems — the Ballasted Ground Mount System (GMS) and the Large-Scale GMS (a penetrating system) — can both be assembled and installed quickly. The ballasted system situates panels one-by-one in portrait orientation while the penetrating system uses four panels on top of each other in landscape orientation. The Ballasted GMS works well on landfill caps, but it was not chosen for the Ludlow or Easton landfill projects. Instead, Borrego and SunLink decided a reformatted version of the Large-Scale GMS would be more efficient for the scale of the landfill projects.

“If you have the right crew, the right equipment, the right project, we believe that the four-in-landscape [orientation] is more cost-effective in terms of installation,” Reznikov says. “Borrego thought, because they know how to build these projects, they were going to be better off with the four-in-landscape product.”

UNDERGROUND MOVEMENT

UNDERGROUND MOVEMENT

The Ludlow project was a 2.6-MW installation, while the landfill in Easton received a 1.9-MW solar installation. Usually projects of that size are installed in long, continuous rows of panels. But differential settling of things underneath landfill caps prevents long rows from happening.

“If you think about things in landfills, things decompose at different rates so it’s not a steady settling that occurs,” Harrison says. “You might have a bunch of material in one section that decomposes quickly, and you get an indentation in the landfill. Eighty percent of the settling occurs in the first 10 years, so we won’t install on a landfill that is less than 10 years old.”

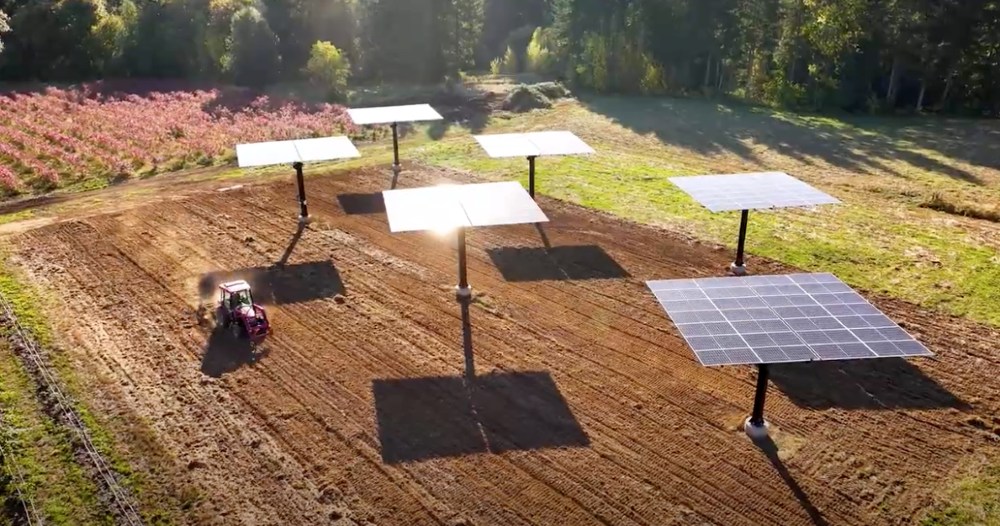

Since settling still happens after the 10-year mark, solar modules are best situated into tables, usually four panels high by five panels wide using SunLink’s system, to accommodate possible movement. The tables are secured to two posts and ballasted a few inches apart so there’s enough space that the racks won’t hit each other when differential settlement does occur.

“We do offer enough adjustably in the system to provide for differential settlement, but with the lifetime of a system at 20 years, we can’t predict everything,” Reznikov says. “We want to make sure if there is an unexpected amount of differential settlement, a two-post, non-continuous system gives a little more flexibility.”

MAXIMIZING PROFIT

There are a lot of added expenses to a landfill-based solar system, including concrete costs for ballast blocks, transportation costs for getting ballast blocks to sites and wiring costs for securing and protecting wire above ground since it can’t be trenched underground. Finding any way to save a few dollars elsewhere on a system is really beneficial, Harrison says.

“It’s already more expensive to construct on landfills, so it really makes sense to maximize the system size as much as you can,” he says. “Maybe you tighten up the row spacing, maybe you use a more efficient module — we’re really focused on driving down the cost of solar.

“It’s already more expensive to construct on landfills, so it really makes sense to maximize the system size as much as you can,” he says. “Maybe you tighten up the row spacing, maybe you use a more efficient module — we’re really focused on driving down the cost of solar.

“SunLink is a good partner,” he continues. “We really work together with them to drive down the cost and come up with the best solution. The SunLink system has a better coverage ratio, and we can fit more PV on the site.”

SunLink is committed to meeting its customers’ needs.

“We’re there to support our customers with whatever they need,” Reznikov says. “We’re here to help our customers solve problems. We pride ourselves on going the extra mile to get a project to a successful state. We have the engineering chops to answer the need.”

Since these two Massachusetts projects in 2012, SunLink has continued to partner on landfill installations. Reznikov says the company is working on around 20 MW of landfill projects in 2014.

“We’ve seen the market expand quite a bit,” he says. “Before it was a couple hundred-kilowatt jobs. [Then] with Borrego we saw almost 4 MW, and we’re seeing that expand more and more. When we look at landfills or brownfields, that’s just land folks can’t necessarily use. It’s a perfect place for solar. It’s something that we believe is going to keep growing. Given the number of landfills out there in the U.S., developers are focusing on that. They’re growing, and we’re growing with them. We’re big believers in the landfill space.”

Comments are closed here.