Consider the source part 1: The fight against forced labor in polysilicon

Solar PV panels — the symbol of the industry — are a bit of Rorschach test. What do you see when looking at one? The starting point of renewable energy generation or the end of a murky supply chain? A marvel of scientific innovation, or the shortcomings of global mass production? Maybe all of it. A solar field is large, its modules contain multitudes. All we can say for sure is every solar panel needs photons to generate electricity, the same photons our eyeballs use for sight. In our Summer edition of the magazine (coming soon – subscribe here), we’ll illuminate a few solar panel production and procurement issues for you to see. Here’s a peek at part 1.

Forced labor in polysilicon

In June, the United States government took action against polysilicon from China’s Xinjiang region, based on information it has regarding the region’s use of forced labor (China continues to deny this is happening). Here, we’ll put these U.S. enforcement actions in context and set the stage for what comes next.

What’s happened so far

Action 1: The U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs published a Federal Register Notice updating its “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor” to include polysilicon produced with forced labor in China. This was notable because the update came on its own, outside the standard two-year cycle for updating the list.

Action 2: The Bureau of Industry Security (BIS) added several companies to its Entity List: Hoshine Silicon Industry (Shanshan) Co., Ltd.; Xinjiang Daqo New Energy, Co. Ltd; Xinjiang East Hope Nonferrous Metals Co. Ltd.; Xinjiang GCL New Energy Material Technology, Co. Ltd; and Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps.

This is the least consequential of the actions as it deals with the export of materials from the United States, not imports. Historically, this list is for incentivizing good behavior, but the Trump administration started to expand its use to control more market activity.

“It’s a list that will evolve a lot,” noted Kevin Wolf, export control attorney, partner at Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP on a SEIA webinar. “I think you’ll see more controls on end uses that have a human rights focus even if the underlying technology is not listed.”

Action 3: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) issued a Withhold Release Order (WRO) on silica-based products made by Hoshine Silicon Industry Co., Ltd., a company located in Xinjiang, and its subsidiaries. All U.S. ports of entry have been instructed to immediately begin detaining shipments that contain silica-based products made by Hoshine or materials and goods derived from or produced using those silica-based products.

The specific name of the company matters, noted John Smirnow, general counsel and vice president of market strategy for SEIA. “This is just a Xinjiang-located subsidiary of the Hoshine parent company that has operations around China, and the action only applies to it, not the parent company.”

So far, anyway.

Is this just the beginning?

Yes.

All of these actions are just one part of a much broader focus on the Xinjiang region by the U.S. government. CBP’s forced labor investigations have produced six WROs this year, with tomatoes and cotton being other high priorities. Currently, 35 of 49 active WROs are on goods from the PRC, and 11 WROs are on goods made by forced labor from Xinjiang.

These solar-related actions look like a calibrated effort of sorts by the Biden administration. Given the options they had, Mark Herlach at Eversheds Sutherland, an attorney focused on energy, international trade and defense matters, described these initial actions as “relatively constructive and not as burdensome as feared.”

“The Biden administration is navigating a few goals here,” he says. “One is to ensure workers’ rights are respected and forced labor isn’t used to make products that enter this country, and the other is to reduce carbon and encourage the build out of renewable energy infrastructure.”

Judging by how these cases normally play out, this is likely just the start of an incremental process. Herlach continues: “A question is whether over the long term they might try to use other techniques to create more difficulties.”

The administration could have imposed sanctions, for example. “That would be the most troublesome from the standpoint of Xinjiang companies and would be much more complicated, so it’s telling that they did not do that,” Herlach says.

The actions that do come next will depend on what other companies the government links to forced labor. Further action might also depend on the impact these first actions have on the market, in terms of incentivizing a domestic solar supply chain. See the sidebar on page 12 for one legislative effort to get that going.

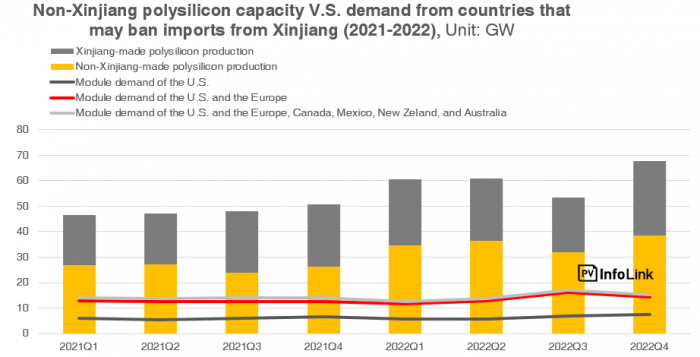

How much polysilicon is this?

According to InfoLink, around 80 percent of the world’s polysilicon supply comes from China, with Xinjiang comprising 45 percent. That is a lot. But when you consider Figure 1 on page 9, the poly sourced outside of Xinjiang is sufficient even in the worst-case PV demand scenarios. Of course, as more sanctions come from the U.S. and other countries, demand for polysilicon in non-Xinjiang regions will obviously be much stronger. Europe is considering mandatory human rights due diligence, where companies could become liable and face penalties on what occurs in their supply chain.

Regarding just Hoshine Silicon Industry Co., Ltd., the CBP identified about $6 million in direct imports to the United States and about $150 million linked to other solar equipment using Hoshine material in the last year. That’s $6 million of the $8 billion in solar cells and modules imported in 2020, according to SEIA.

But these stats might not tell the whole story considering how difficult it is to trace the PV module supply chain (and that close to 98 percent of ingot wafers come from China). S&P Global Market Intelligence paints a different picture in its recent reporting: “It’s very hard to pinpoint … one manufacturer that could not be at risk” of exposure to Hoshine, said Frédéric Dross, VP of strategic development at auditor Senergy Technical Services, on a June conference call hosted by ROTH Capital Partners LLC. “There is a probability that every single [solar] module that enters the U.S. is potentially affected.”

How are these enforced?

With cotton, the CBP issued detention notices for a handful of import entries for one company. They also requested information from importers, conducting Risk Analysis and Survey Assessments (RASAs), which are deeper inquires to probe compliance policy or procedures.

“Importers should expect to receive CF28s, asking if you know where the poly silicon came from,” Smirnow says. “They will want to know how you ensured the products you imported don’t include forced labor, right down to specific products. They will pull a panel out of a container, look at a serial number and want to know where the poly came from and provide evidence for that.”

What should I do right now?

In October 2020, SEIA started calling on the industry to move solar supply out of China’s Xinjiang province. By April 2021, the group launched the Solar Supply Chain Traceability Protocol, a set of guidelines to help provide “assurances that solar products are free of unethical labor practices.”

That Traceability Protocol is designed to provide credible info concerning the origin of materials that comprise the product being imported, meeting what the CBP needs to see. That third-party verification matters because, unless it was stated in a contract to do so, module makers had no obligation to trace the origin of materials this far upstream until now. Firms conducting these traceability audits right now include Clean Energy Associates (CEA), Synergy Trade Services (STS) and PI Berlin.

“Since [the CBP] has identified what they don’t want to allow into U.S. commerce, with a full transparency and traceability program that shows that nothing in the product is made by Hoshin, we expect Customs will release that product into U.S. commerce,” says Paul Wormser, VP of technology for CEA, which developed the Traceability Protocol for SEIA.

CEA has a long history of being in factories, monitoring solar and storage, employing almost 100 engineers to examine how a factory is running from a quality standpoint.

“We know where companies don’t keep great records or don’t always meet their own quality requirements,” Wormser says.

Going forward, will it be difficult for them to fully trace a module’s material all the way back to the poly producer if the module maker itself hasn’t? In some cases, yes, but it’s all doable, Wormser says. In the cases where visibility isn’t possible, or where an ingot provider won’t let an auditor into their facilities or won’t provide the appropriate information, well, that’s also useful information for the buyer.

“If you can’t get the full transparency because someone in the chain refuses to comply with your request, then you have to make a choice about whether you continue to buy that product — and now with the WRO, that makes that decision a lot easier,” Wormser says. “If a facility won’t allow access to a physical audit, you can decide to just trust the documentation, but I would be surprised if that’s going to be sufficient for U.S. Customs. Customs really wants more than the supplier’s word, and if they can’t somehow arrange access to some part of the supply chain then there is risk that Customs is going to determine that your information is not satisfactory.”

Wormser does think the level of upstream supply transparency and traceability has already started changing prior to the WRO, and he expects that to continue. Supply chains are now highly incentivized to ensure compliance to sell in the U.S. market.

“It was opaque last year because this wasn’t an ask, but now it is. We are seeing legitimate efforts by module makers to become more transparent,” he says. “If you’re making wafers in China, you want to make sure a portion can be sold to the United States. If the U.S. wants transparency, you’re probably motivated to have it even if you didn’t before. And I would say just getting past Customs is not sufficient. If your company view is ‘thank goodness Customs didn’t find anything,’ that’s a naïve position.”

The PV buying landscape is rapidly evolving. Beyond Customs, customers and investors are demanding this transparency too.

“This is a serious issue,” says Wormser. “This is also an opportunity for the industry to become more transparent which is absolutely fundamental for carbon tracing, finding root cause of defects and recycling — and the whole idea of consumers being more and more interested in where things were made.”

In part two we look at the embodied carbon of solar panels.

Comments are closed here.